The wiki paradigm is half baked. One of the main challenges companies and individuals always have with their wikis is organization. Why? Because organizing a wiki wasn't part of the spec. Back in 2003 Ward Cunningham, the inventor of the wiki, gave an interview where he admitted this:

There is an organization there, and the organization can be improved, but it isn't highly organized. - Ward Cunningham

A wiki is just a way of linking and composing information. This is what makes the system so flexible, adoptable, and versatile. However, this simplicity comes at a cost. No matter what tool we use, we seem to always have problems either knowing where to put a document, knowing where to find it again, or both.

So, in this post, I'm going to discuss some high level strategies and concepts regarding organizing a wiki or knowledge base. I hope that by explaining these paradigms and practices, you can be better equipped to design a system that works best for you and your collaborators.

Let's get started by discussing...

The stakeholders of a wiki.

Whether you're creating a wiki for personal knowledge management (PKM) or for keeping your team on the same page at work, there are two main stakeholders of a wiki: authors and readers.

Authors care about capture. They want to be able to write something down with as little friction as possible. They crave speed and don't care much for structure. They want to get something out of their head and onto a page quickly.

Readers care about retrieval. They want to be able to easily explore and search the wiki. They crave structure because it means they don't have to dig through documents or distract collaborators to get what they need. Their number one priority is finding things fast.

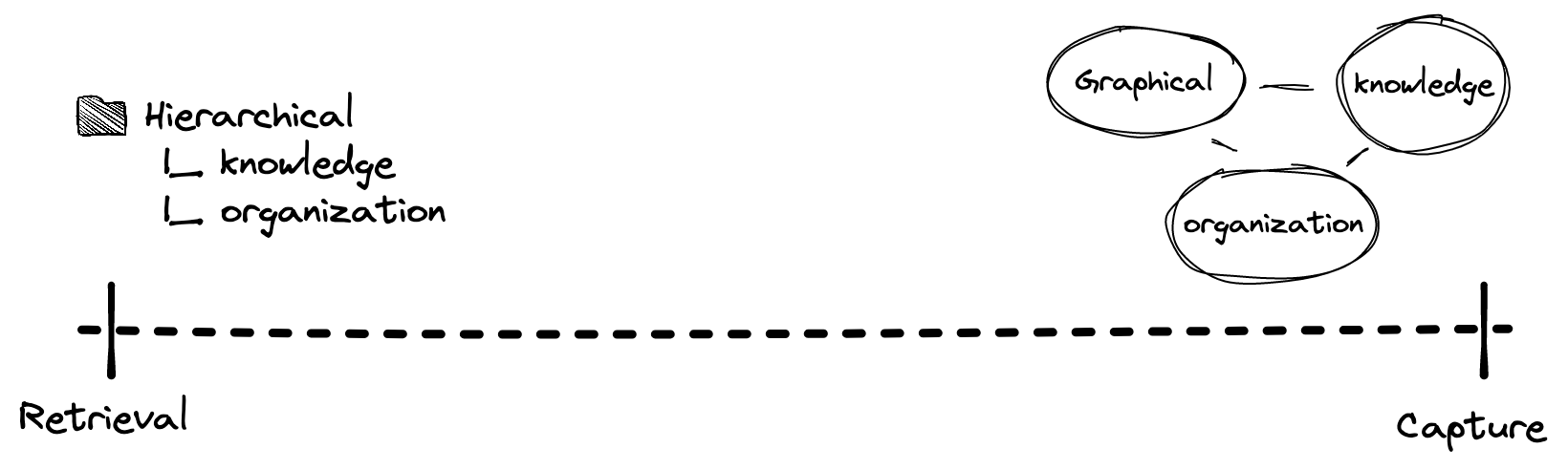

Obviously, in a true wiki, everyone is both an author and a reader. However, thinking about these roles separately helps us identify and design for these two distinct functions: capture and retrieval.

As we'll see, this is no easy task, because capture and retrieval live on opposite sides of...

The knowledge organization spectrum.

The ways we structure and organize information lies on a spectrum between two principle patterns: hierarchical knowledge organization and graphical knowledge organization.

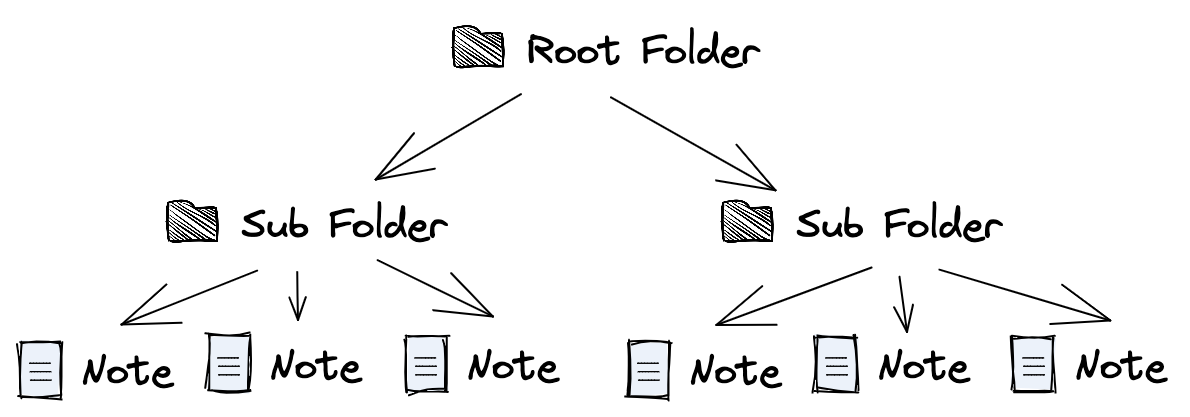

Hierarchical knowledge organization (HKO)

This pattern is very familiar to us; it's our basic folder system. We create and follow a bespoke, distinct schema that puts documents in folders and folders in folders. Each document - or "node" if we map this structure - can have a direct parent and direct children only.

This method creates a tree of information that's easy to traverse. In order to find something again, all we have to do is know its place in relation to each layer of the tree. Retrieval is trivial as long as the schema is maintained. However, this strict structure makes capture more complicated.

Creating a new document means thinking about what type of document it is and where it will live once it's finished. That decision fatigue is felt by authors and discourages them from writing down an idea quickly or creating a document that doesn't fit the mold. This friction can be frustrating and cause some people to reject the inflexibility of the system. People either start adding documents outside the bounds of the bespoke structure or they stop writing in the wiki altogether.

This conflict is what can cause many tools that implement HKO (Google Drive, Dropbox, OneDrive) to feel messy and chaotic. Without routine maintenance, pure HKO based systems quickly loose their ability to make finding and retrieving information easy.

That's why I think they're best used in situations with predefined information schemas with documents that don't change very often. They're great for "company wikis" that are more about creating a collaborative FAQ or a cohesive company handbook. They're harder to use for creating a collective knowledge base that employees use every day.

This tradoff is the primary reason we leave tools like Google Drive as we grow. The sheer amount of documents being created becomes too much to constantly curate. So, we move towards tools like Confluence, Notion, and Slab. These tools take a different approach that is more condusive and aligned with the traditional wiki format.

Graphical knowledge organization (GKO)

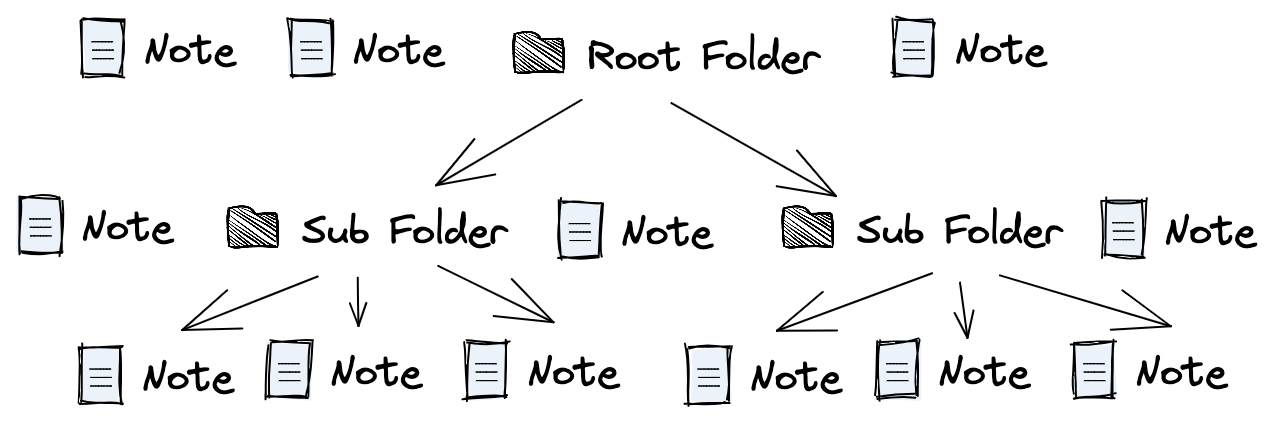

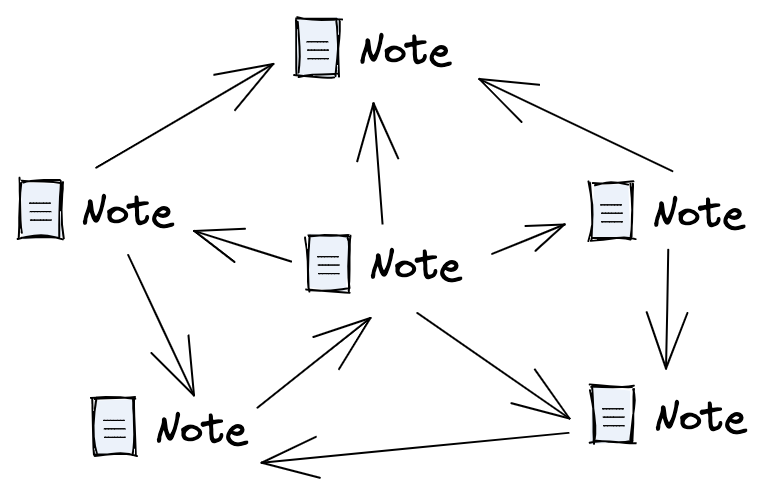

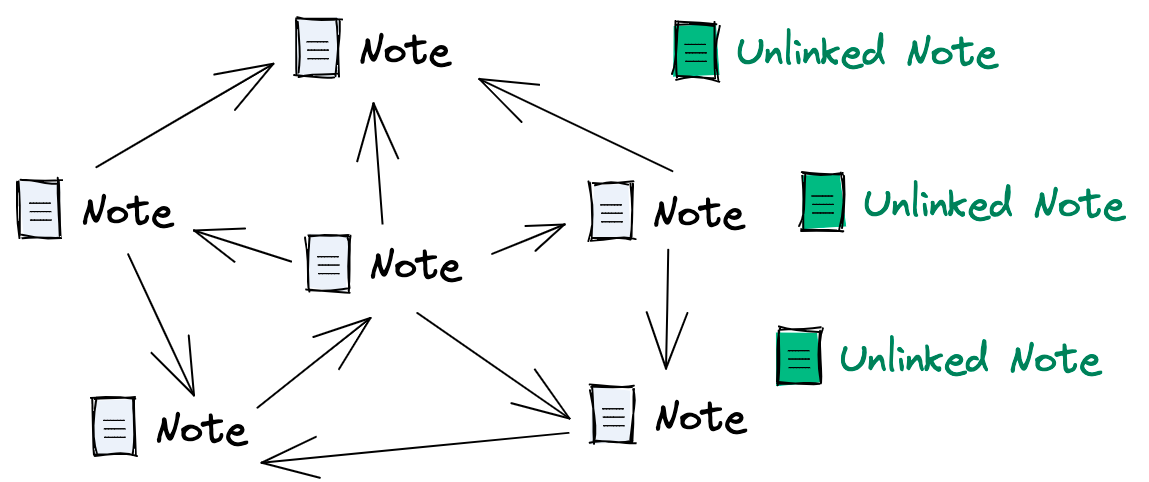

Although we don't think about it as often, graphical knowledge organization is also familiar to us; it's the internet. We create and connect documents with links to any other document. These documents - or "nodes" - don't have a pre-defined structure or hierarchy. The structure emerges on its own based on the connections we make between them.

This method encourages us to fill out this web of knowledge. Capture is encouraged because connecting new documents to the collective helps us see how common concepts relate to each other. Seeing these relationships grow and unfold can spark our creativity and help us have novel and interesting ideas.

However, as you might expect, this benefit usually comes at the cost of retrieval. Reading a graphically organized knowledge base is a real challenge. Ward Cunningham explains why really well,

The first thing you have to understand is that because we made wiki easier for authors, we actually made it harder for readers...the feeling for a reader is one of foraging in a wilderness for tidbits of information. - Ward Cunningham

Where sticking to a strict structure can be frustrating for authors, this foraging can be infuriating for readers. The structure in GKO is conceived and not controlled. It's opaque, not easily understood, and even changes over time. In some situations, this means people - especially those new to the wiki - might never find what they're looking for.

One might think that our modern, advanced universal search algorithms have put this problem in the past. Rather than search being solely limited to the name of a document - which was how most wiki search worked in the early 2000s - we can now search across names and content.

Search sounds like a silver bullet. But in practice, fuzzy search just means we have to comb through more results to find what we're looking for. Search is also a useless tool for most new people at a company who don't yet know the search terms.

Just like how having to stick to a strict structure can cause authors to stop writing, no semblance of structure or curation of content can cause readers to stop reading. In either case, whether no one writes or reads, the result is the same: the wiki becomes useless.

So, what's the solution? Well, that obviously depends on the needs of you and your company. However, in general, most experts recommend...

Striking a balance.

Figuring out where you and your team are most comfortable on the spectrum between capture and retrieval is vital to the health, longevity, and usability of your wiki. In almost all cases (even PKM), maintaining a wiki is a team sport. So, pick a method and develop practices that your organization can sustain.

This is the part of the post where I want to make recommendations for how to strike that balance. But the truth is that it's almost impossible to make specific recommendations when it comes to knowledge management. Implementing an effective wiki/knowledge base hedges on three highly variable factors:

- The tool you choose for your wiki.

- What you're actually writing in your wiki.

- The culture you cultivate around knowledge management.

It's obviously hard to take a more capture-focused, graphically organized approach using a folder-based tool like Google Drive. It's probably better to take a more hierarchical approach if you work in a field like law or accounting where documents are more templated and easier to categorize. Finally, if you work in an organization that tends to lack trust or transparency, you'll likely have a difficult time getting people to use a highly collaborative, communal tool like a wiki.

So, the best thing I can say is to keep learning about your needs. Understanding the problems your organization is experiencing and where the breakdowns in communication are occurring is the most important piece of knowledge management.

What side are you on?

I'd love to know more about which side of the spectrum you or your company currently sits on to balance capture and retrieval. Personally, I lie much further on capture-focused, graphically organized side of the spectrum.

Send me an email or reach out on Twitter. I'm truly very curious to hear about your experiences with company wikis and knowledge management.

Until next time.